Embracing the “engaged and public humanities” and abandoning “alt-ac”

Lauren Frey is a candidate for the M.A. in the Department of English at Georgetown University, where her research focuses on modernist poetry, the women’s suffrage movement in the United States, and notions of the public sphere in early 20th-century American culture and literature.

This past January, I attended the MLA Conference as project manager for the Connected Academics task-force at Georgetown University. One semester into my master’s in English, I was eager to engage in conversation with other graduate students who were interested in the pathways students can take to find jobs beyond the professoriate. Attending the Showcase of Career Diversity on Friday afternoon, I got caught up in a discussion with a small group of graduate students about the terms used to describe those pathways.

One graduate student bemoaned the term “alt-ac” for reasons that have long been acknowledged by Bethany Nowviskie, Director of Digital Research & Scholarship for the University of Virginia Library, who coined the term in January 2010 to replace “non-ac.” Since then, “alt-ac” has also become less popular in academic circles, mainly because it seems to privilege the academy. Also privileging the academy in self-condemning and self-exiling ways are the terms “out-ac,” “ex-ac,” and “post-ac.”

Perhaps more importantly, “alt-ac,” like these other terms, is harmful because it often seems a misnomer. Versatile PhD shows this by labeling careers in institutional research, K-12 education, e-learning and instructional design, writing and editing, translation, and publishing as “Non-Academic,” when often these positions simply take place in another area of the academy or are interconnected with the academy. To use “alt-ac” to apply to any position other than a faculty position, including other positions at universities and educational institutions, undermines our understanding of what new PhDs in the humanities are actually doing after completing their degrees.

In the discussion at the MLA, another graduate student shared her aversion to the term “public humanities.” The critique finds the use of the word “public” a redundancy, as if “public” silently accuses the humanities of attempting to be a completely private enterprise, where the scholar is constantly bowed over her book, disengaged with the world. I thought this was a good point, but it struck me as almost an opposite impulse to the aversion to “alt-ac.”

This is because, even while “alt-ac” seems to fail to acknowledge the power of the living public, private, and non-for-profit enterprises beyond the academy in which a PhD is useful, “public humanities” could fail to acknowledge that the act and art of mastering a humanities discipline inherently aims to give one an ability to think and engage with the world in a public-oriented way. In and outside the academy, the process of researching and interpreting a piece of literature requires an engagement with a public of other readers, whether that public is one or one thousand years old, a mass or a silo. This self-awareness that one is posturing toward some public, not just toward a text, is simply best practice in the work of reading, writing, instructing, and thinking as a scholar. Thus, by saying “public humanities,” one can seem to discredit the implicit importance and cultural effectiveness of this sort of knowledge-making.

I left the MLA both encouraged and challenged by that conversation. At the very least, I developed a new sense of urgency about using the best terminology for thinking about what I am doing in a humanities discipline and why it is important to help contribute to an academic culture that values care for the language we use to describe it.

When one scrutinizes words and names, one helps facilitate the evolution of language and terminology to reflect an evolving knowledge. When new experiences and facts emerge out of some inquiry, so should terminology. In this sense, the aim of language is not only to record experience, but to aid in the communal comprehension of those experiences for the sake of future action.

The new “inquiry” that has emerged, in the past decade or so, involves the employment of those with advanced graduate degrees who wish to work outside of or alongside of the academy. In choosing to turn our knowledge and skills towards various “public” uses, we are not (“only,” let’s say) referring to “Shakespeare in the park” nor (“only,” again) to paid research positions for corporations. In other words, the goal of advanced training in the humanities transcends producing new knowledge or developing particular research skills. Rather, it attempts to shape a human being into someone who has a particular set of values that can lend themselves to real-world problems.

Research is a skill, but the humanities pursues the knowledge of how and what to research and what those things mean for the public good. In this sense, rethinking the nature of advanced scholarship in “the humanities” — while using the most collectively helpful terms to name that rethinking — is important.

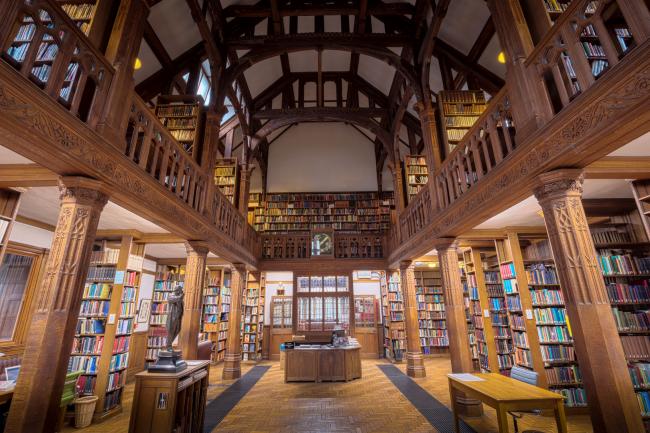

But few graduate students in the humanities have been trained to think about their work as relevant to pursuits or publics beyond academia, even though they really are trained to do that work. By the graduate level, students should be strong critical thinkers, exploring everything that is to be known about the enterprises they are involved in. Those enterprises can and often do lead to rewarding careers in libraries, think-tanks, educational consultancies, and corporations. They may, but probably will not, lead to tenure-line positions at universities. Humanities scholars need to view their educations not as definite pathways to a professorship, but as rigorous training that will allow them to contribute to the greater thing humans share and that the academy can stand for only to an extent: the development of knowledge.

Since this conversation at the MLA, I have continued to hear and read the frustration over the use of “alt-ac” to refer to that journey just described. During Georgetown’s three-day inaugural Graduate Certificate in the Engaged & Public Humanities, my conversations with the MA and PhD students across the country affirmed that “alt-ac” is a discouraging term.

Yet despite this aversion to it, it is still the go-to in articles and blogs, because it is the most widely understood. Meanwhile, other terms such as “beyond the academy,” “beyond the professoriate,” “non-professorial employment” have emerged. Along with these more precise and positive terms, our team at Georgetown has been using the term “beyond academia.” While it has been said that these terms do not fully acknowledge the sense of identity loss when one is no longer “in academia,” it reflects a fair repositioning of the academy as something that can be moved past without all being lost.

The opaqueness of “public humanities” is perhaps a problem that can only be resolved when the impact of humanities projects and initiatives, such as those on the new NHA database Humanities For All, becomes stable and lasting enough to quantify. At the moment, these projects expose the need for the term “public humanities” by bridging the gaps between scholarly work, civic engagement, and collaboration with artists and various social publics.

Meanwhile, work in the movement called “Engaged and Public Humanities” continues to grow. At Georgetown, we use this term as we seek to facilitate a space for humanities scholarship to blossom in the public sphere in exciting interdisciplinary ways.

As we move forward, humanities graduate students and departments can embrace the evolving language that will describe efforts to bring humanities approaches to public issues and celebrate the innovative work of graduate students who pursue varied career outcomes. To go beyond “alt-ac” will require us to rethink how we value these careers — and the scholars pursuing them.

Whatever term we choose should reflect an understanding that varied career trajectories for graduate students in the humanities are of equal value to the work of the professoriate.