Reclaiming the Gems of Ottoman History for an Inclusive Public Humanities

Ottoman Humanist Mustafa Âli (1541-1600)’s Quest for Justice and Empowering the Public

By Said Salih Kaymakci

MA in History, Georgetown University

PhD Candidate in History, Georgetown University

At Georgetown University Graduate School’s Engaged & Public Humanities certificate program where forty-nine graduate students and leading scholars of humanities from across the nation gathered, we discussed the ways to give a public face to our works. We thought about our PhD work beyond the academia and not falling into the “Quit Lit” in order to ensure a viable future for the humanities in an environment of sustained attack on scholarly expertise and declining interest in humanities education.

One of the questions sparked by this discussion in my mind was how to make public humanities in the West more inclusive with regard to Islam and Muslims, as a Muslim immigrant in America doing PhD in History. This is an important matter in a world of increased Muslim presence in the West and ongoing turmoil in the Islamic world: creating anxieties among European and American societies, feeding the rise of alt-right/far-right, and causing a shift in the political scene away from liberal democracy towards nationalism and authoritarianism.

Without tackling questions about Islam and Muslim’s relationship with modernity and modern world, finding a rightful place for the Islamic tradition within the Western humanities discourse and making the public audience of humanities inclusive of the Muslims, the future of democracy and humanities are at risk. For Muslims who want a democratic and prosperous future, such an undertaking is needed . When modernity itself is being critiqued for its failures and calls for “refashioning the modernity” are made, a Muslim/Islam inclusive public humanities would help to make our world a better place by helping to deal with and solve some of the problems of modern age. Thus, what is at stake is soul-searching about modernity for the Muslims and non-Muslim Western public alike.

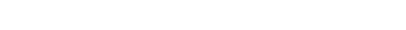

As an historian of Turkish origin of the early modern Ottoman State, I would like to bring an Ottoman bureaucrat cum humanist scholar Mustafa Âli (1541-1600) into light as an attempt of making public humanities Muslim/Islam inclusive. Âli was well-versed in Islamic humanistic tradition such as history, literature, philosophy, ethics and law. His works were interdisciplinary using elements of all these fields to express his concern for the human condition and further his political agenda of achieving justice in the society. Âli’s look into the ancients — which included the Greeks, the Chinese and Persians along with earlier Muslims and Ottomans — as role models reminds one the Renaissance and early modern era humanists. He was aware of the changing times. How to solve the problems of a different times by reviving the ancient model and adapting to a new reality was a central problem that joined Âli with his Western European contemporaries.

The Ottomans and Europeans of Âli’s times shared the early modernity with its challenges and disorders. A similar debate about the limits of royal power took place in the Ottoman and European dynastic realms. Âli was a constitutionalist making case for an ancient Ottoman constitution in his histories to limit the royal power similar to English antiquarians. In his work on the different professions of his time, he treated the post of sultan as a profession among others to an equalizing effect. He wrote a history of Islamic States where he focused on the fall and rise of a dynastic state with adherence to and deviation from justice. For Âli, it was the public approval and disapproval which gave rise and fall to a state in a contractual relationship which was broken when the dynasty deviated from justice. Keen to show the public’s role in state-making, Âli emphasized that he wrote his history in vernacular Ottoman so that it would be read at public gatherings. Âli’s world experienced what a modern historian called “the expansion of the political nation” , and Âli was eager to empower the public for his constitutionalist agenda.

Being concerned with the nature of the civic society at his time and to support his agenda of public empowerment, Âli wrote books of etiquette of public gatherings where he depicted his ideal form of public sphere. He was critical of the Ottoman sultans who secluded themselves from the public and abandoned their predecessors’ practice of dining with the ruling class, which he saw as a violation of both the prophetic and dynastic customs. Âli stressed that a king who does not receive the public approval cannot be considered a king and the Islamic legal principle of king being the shadow of God on earth was tied to the king’s adherence to sharia. In these works, he recognized the introduction of the coffee and coffee houses into Constantinople after 1553 and how they quickly became a new public sphere as a place of meeting both for the learned, the poor, and dissolute. Yet, he defended the coffee houses as a place of good conversation, calling the coffee “the magical drink of the righteous”, and the hearts of the followers of the Sufi path are tied into it. Âli wanted his works to be read at them.

What made Âli a humanist is also his view of the public. He declared the people his time as brothers with respect to their humanity, loving and sincere friends due to their familiar habits and relationships, neighbors because of their nearness, and that they were connected with their fleshes and lives thanks to their common genealogy. Âli had a negative view of the slavery and claimed that a slave and sultan were equals as the slaves at the gate of God with sultan being just the figurative lord in the world and God the real Lord. Yet, Âli’s ideal order was an aristocratic constitutional state, not Habermas’s bourgeois constitutional state or a modern liberal democracy. His understanding of justice was different than modern conception of social justice. While opposing government oppression and seeing this as a form of injustice, for him justice also meant putting the things into their rightful place, that is, preserving the supremacy of aristocracy in a hierarchical social order in the Aristotelian fashion and ensuring promotion for himself in the Ottoman bureaucracy. However, Âli’s European constitutionalist humanist contemporaries had a similar worldview and concerns. It was a world in which the result of the battle between absolutists and constitutionalists was far from being clear.

One can even draw similarities between the conditions and motivations of Habermas and Âli. Similar to Habermas who developed his theory of bourgeois constitutional state with its public sphere long after its “collapse” when he felt Western project of modernity is under threat, Âli wrote about his ideal Ottoman constitutional state at a time when he perceived the Ottomans deviated from their ideal ancient regime and disorder reigned in the Ottoman realms threatening the very existence of the Ottoman state, civic society, and culture. Both Habermas and Âli hoped to revive their respective ideal public spheres and political systems in their perceived worlds of disruption.

Despite all the differences Mustafa Âli displayed from modern activists striving to achieve social justice and advance democracy, placing him in his “rightful place” by showing his humanistic agenda and concern for the public and expansion of public sphere and similarity to European constitutionalists and even Habermas, is an important endeavor in tackling with the modern-day questions about Islam and Muslim’s place in the modern world. At least showing a common past of Islamic and the Western worlds would help us to demonstrate Islam also accommodates humanism and a deep concern for justice, and Muslims are not essentially anti-democratic regardless of the divergent worlds that appeared later under specific historical circumstances.